Sustainability

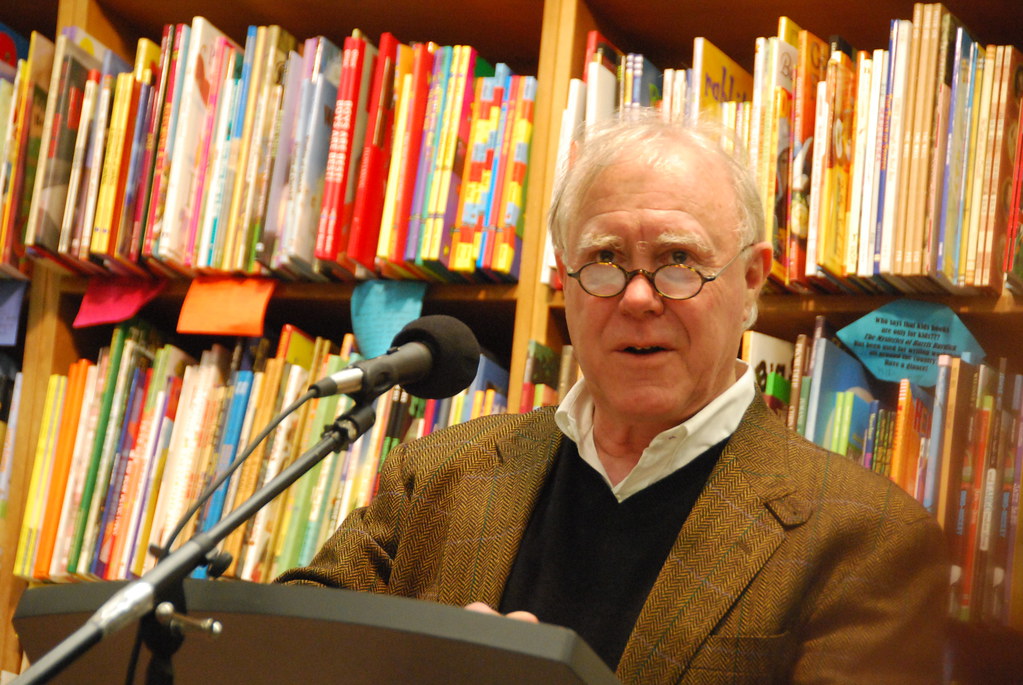

Edward Hessler

The threat of anthropogenic climate change has a way of narrowing attention on the planet's health to a single cause. However, this can also serve as a distractor.

A recent commentary in Nature for 11 August 2016 reported on an analysis of threat information on more than 8000 near-threatened or threatened species from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It includes both plants and animals. The study led to a somewhat surprising finding.

The biggest driver of biodiversity decline appears not not to be anthropogenic climate change. The main drivers familiar bad guys: overexploitation (commerce, recreation, subsistence) and agriculture (production of food, fodder or fuel). Only nineteen percent of the species studied are affected by the various effects of anthropogenic climate change.

|

| Deforestation. Image from Wikimedia Commons. |

Maxwell is a graduate student in geography, planning and environmental management. Fuller is a professor of biological sciences. Brooks is head of science and knowledge at the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Watson is a professor of geography, planning and environmental management.

The data are beautifully summarized in a table of circles of various sizes which show the number of species and the threat. The categories are overexploitation, agricultural activity, urban development, invasion and disease, pollution, system modification, climate change, human disturbance, transport and energy production. Each of these is further subdivided into sub-categories.

All studies have limitations and the authors point out three. The sample is not random. Threats are treated as discrete when in fact they are not isolate. The threats will change over time. Red List assessments are projected only over a ten-year period or three generations. This means that anthropogenic climate changes will be modest for short-lived species. The authors remind us that climate change will become more dominant in the future.

Some solutions the authors suggest are that funding actions should give priority to the largest, current threats. They note that there are effective tools already at our disposal. These include sustainable harvesting, enforcement of regulations, maintenance of international policy agreements, protection, agricultural management that includes threatened species, pesticide/fertilizer regulation, reduction of food waste, and the certification of agricultural sustainability.

The authors close by writing that conservationists, weary of tackling herculean, long-standing problems, could be forgiven for being drawn to newer ones. Nonetheless, we appeal to all concerned with the sustainability of life on Earth to take stock of the current balance of threats--and refocus their efforts on the enemies of old.

Tradition, politics and economics are formidable obstacles to some of the changes suggested above but we are learning that there are many direct benefits for us by modifying past practices, ones which are all too easily overlooked under threat of global climate change.