STEM

Health

Medicine

History of Science

Nature of Science

Edward Hessler

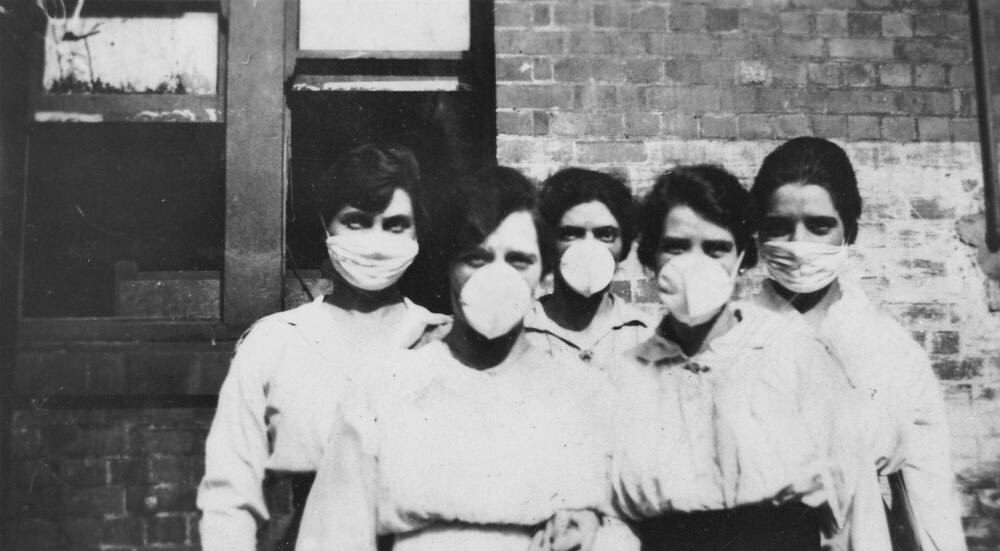

The origins of the 1918 pandemic influenza epidemic, the so-called Spanish flu, are not known and perhaps never will be. The origin story I know is that it emerged in Haskell County, KS, in January 1918, jumping from another host to humans. There are other claims, including some from other countries.

There is a new development in this story and it was reported on by Helen Branswell in STAT (December 5, 2018). What follows is the short version.

University of Arizona Ecology and Evolutionary Biology professor Michael Worobey, who has an interest in disease origins, used a very familiar tool, the Internet, to search for any descendants of William Rolland, a WWI military doctor. A year before the outbreak of the Spanish flu, Rolland had reported on an outbreak of an unusual and fatal respiratory illness. Worobey's curiosity was whether any of Rolland's human tissue slides from the sick had been saved.

In this age of electronic information it may not surprise you that it wasn't long before Worobey received a reply. Retired family physician, Dr. Jim Cox, had a collection of Rolland's human tissue slides which had been handed down and saved for several generations. Cox is married to Charles Rolland's daughter.

University of Arizona Ecology and Evolutionary Biology professor Michael Worobey, who has an interest in disease origins, used a very familiar tool, the Internet, to search for any descendants of William Rolland, a WWI military doctor. A year before the outbreak of the Spanish flu, Rolland had reported on an outbreak of an unusual and fatal respiratory illness. Worobey's curiosity was whether any of Rolland's human tissue slides from the sick had been saved.

In this age of electronic information it may not surprise you that it wasn't long before Worobey received a reply. Retired family physician, Dr. Jim Cox, had a collection of Rolland's human tissue slides which had been handed down and saved for several generations. Cox is married to Charles Rolland's daughter.

Worobey has had ten of the slides for a few years. He and his team have been developing a technique to look for the influenza virus in the tissue samples without destroying the slides. You likely remember glass slides with their delicate coverslips from a biology course. On slides one saves the slip covers are glued permanently to the supporting base. They are saved as records and also for use in teaching.

Branswell reports that Worobey "believes a flu virus with the H1 hemagglutinin--the surface protein that give a flu virus the H portion of its name--likely started circulating among people in the late 1890s or early 1900s and later swapped genes with a avian flu virus to form the H1N1 virus to have caused the 1918 pandemic." The idea that the Spanish flu H1N1 virus had been making people ill for years before 1918, runs counter to the prevailing ideas. However, there is evidence of an earlier outbreak in the winter of 1916-1917 in France.*

Worobey acknowledges that his quest is a long-shot and that is likely, as Branswell writes, "'we'll just get no result at all. That's something to keep in perspective. But if we find something, whatever we found relative to flu would be really interesting and informative."

I urge you read Branswell reporting for it provides fascinating details on a much more complicated story than described here, e.g., on what informed Worobey's internet search, the nature of the unusual "explosive behavior" the virus exhibits when it emerge, the unusual death curve of the pandemic (a W shape--the central peak captures the deaths of the most vulnerable adults), the use of evidence and the role of a probing curiosity in science. The article includes a photograph of several of Rolland's human tissue slides which appear almost as fresh as the day they were made.

*The N part of the name (neuraminidase)--there are 9 of them--allow newly synthesized viruses to escape from the infected cell and spread.

*The N part of the name (neuraminidase)--there are 9 of them--allow newly synthesized viruses to escape from the infected cell and spread.

No comments:

Post a Comment