Environmental & Science Education

Environmental & Science EducationSTEM

Children

Early Childhood

Health

Edward Hessler

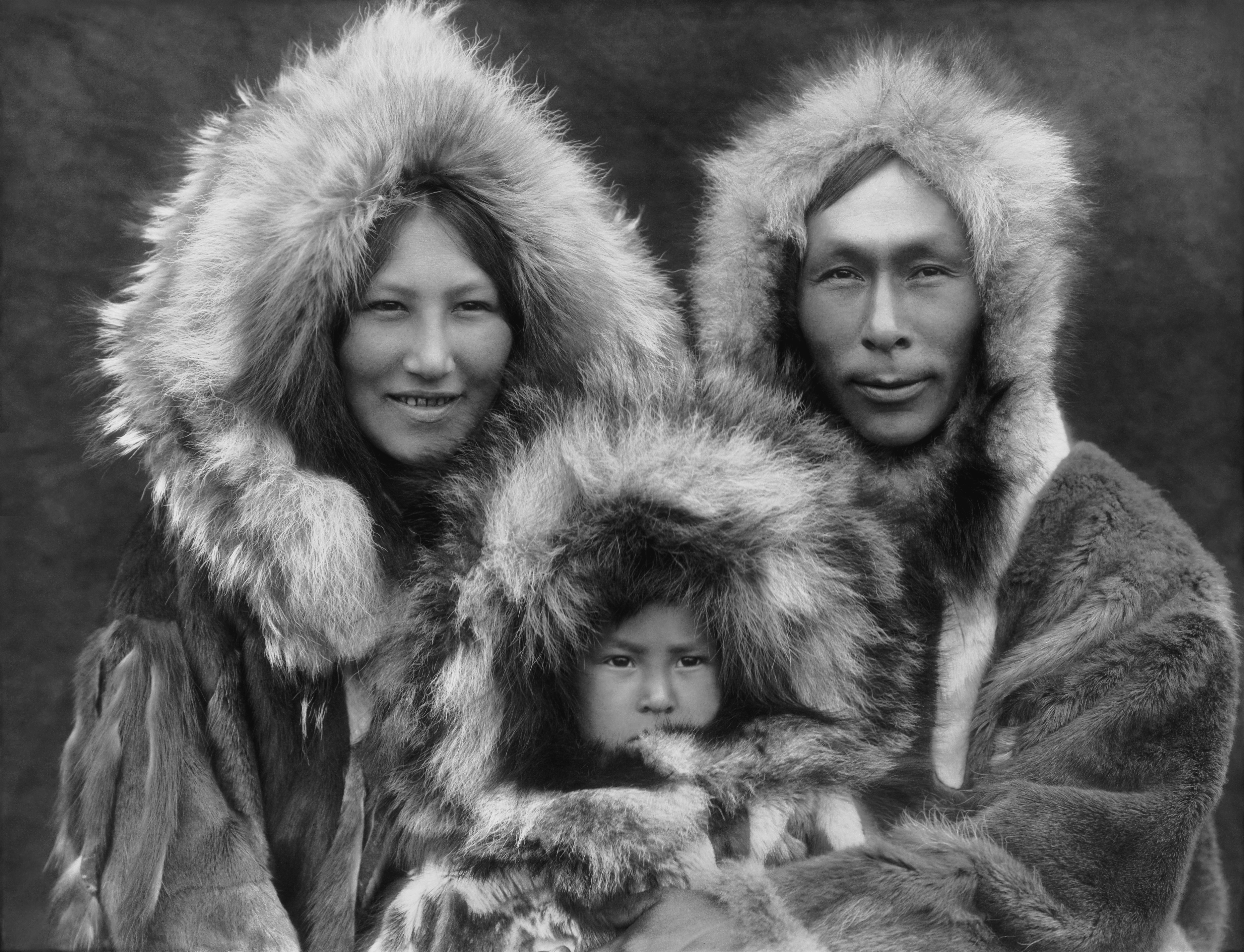

The most recent entry in the NPR series "The Other Side of Anger" explores "How (do the) Inuit take tantrum-prone toddlers and turn them into cool-headed adults?"

This ability of Inuit adults to control their anger was first observed by Harvard graduate student Jean Briggs who lived for on the Arctic tundra with Inuit families for 17 months in the 1960s. It led to the writing of two books: Never in Anger and Inuit Morality Play. A preview of the latter book may be found here.

The clue that led Briggs to begin to unravel how anger is cooled as children grow up was when she noticed a young mother inviting her child to hit her harder with a pebble he was throwing. Briggs wondered about what was going on and came to understand that the Inuit do not yell at or scold their children. Instead they try to figure out what is going on with the child and use stories, small dramas and questions as teaching tools.

"(T)he mom may start a drama by asking: 'Why don't you hit me?'

"Then the child has to think: 'What should I do?' If the child takes the bait and hits the mom, she doesn't scold or yell but acts out the consequences. 'Ow, that hurts!' she might exclaim.

"The mom continues to emphasize the consequences by asking a follow-up question. For example: 'Don't you like me?' or 'Are you a baby?' She is getting across the idea that hitting hurts people's feelings, and 'big girls' wouldn't hit. But, again, all questions are asked with a hint of playfulness.

"The parent repeats the drama from time to time until the child stops hitting the mom during said dramas and the misbehavior ends."

Myna Ishulutak, one of the women interviewed by Michaleen Doucleff for this NPR report was asked whether she was "familiar with the work of Jean Briggs. Her answer leaves me speechless. Ishulutak reaches into her purse and brings out Briggs' second book, Inuit Morality Play, which details the life of a 3-year-old girl dubbed Chubby Maata. 'This book is about me and my family,' Ishulutak says. 'I am Chubby Maata.'"

This parenting behavior is being lost. Doucleff reports that she attended "a parenting class, where day care instructors learn how their ancestors raised small children hundreds--perhaps even thousands--of years ago."

Doucleff's report is a must read because I can't do justice to its fullness. She includes more information, including how stories are used in raising children, comments by professionals, the results of a study on story-telling and the author reports on her experiences on story telling with her daughter. Furthermore, it is richly and wonderfully illustrated.

Clinical psychologist Laura Markham calls attention to the power and value of children's play, describing it as "children's work," an idea I first heard long, long ago when I was lucky enough to attend a day-long session presented by Doris (?) Nash on learning in English infant schools. The power of play as you may recall from other posts, is being emphasized by a number of significant early childhood educators and associations in the United States.

No comments:

Post a Comment